I’ve been pulling apart the DuckTales Game Boy ROM byte by byte using PHP. Just PHP with file_get_contents() and a bunch of bitwise operators. Just out of pure curiosity, and whether it was possible. It’s been… interesting, so I figured I’d log what I’m doing.

It began when I got more into making games, and made a very simple platformer that ended being 50MB in size… but I remember playing DuckTales on GameBoy, and I know those cartridges couldn’t hold that size.

Loading a ROM

A Game Boy ROM is a flat binary file. No compression wrapper, no file system, nothing fancy. It’s just raw bytes . Loading it into PHP is simple:

$this->data = file_get_contents('ducktales.gb');

$this->size = strlen($this->data); // 65,536 bytes

With DuckTales, it’s a full featured platformer, and all in a 64k file. With file_get_contents the whole game is a string in memory. Every byte accessible by index. Want byte number 500? ord($this->data[500]). PHP strings are byte arrays under the hood, which helps makes all this possible.

The Header

Every Game Boy cartridge has a header at fixed memory addresses. Nintendo standardized this so the boot ROM could validate cartridges. We just read the right offsets:

// Game title lives at bytes 0x134 through 0x143

$title = substr($this->data, 0x134, 16);

$title = rtrim($title, "\x00"); // strip null padding

// Returns: "DUCKTALES"

// Cartridge type at 0x147

$cartType = ord($this->data[0x147]);

// 0x01 = MBC1 (Memory Bank Controller 1)

// ROM size at 0x148

$sizeCode = ord($this->data[0x148]);

$actualSize = pow(2, 15 + $sizeCode); // 32KB * 2^n

No magic here. The Game Boy hardware expected the title at 0x134. Most of these locations are documented by many other people, in other languages, but I didn’t write down all the url… so just google ’em if you want.

Finding Text in the ROM

Some text in ROMs is just plain ASCII. You can find it by scanning for runs of printable characters:

for ($i = 0; $i < $this->size; $i++) {

$byte = ord($this->data[$i]);

if ($byte >= 32 && $byte <= 126) {

$current .= chr($byte);

} else {

if (strlen($current) >= 4) {

echo "Found text at $i: $current\n";

}

$current = '';

}

}

This catches copyright strings, debug text, anything stored as standard ASCII.

Most Game Boy games don’t use ASCII for their actual ingame text though. They use a custom encoding where each byte maps to a tile in the font. DuckTales maps it like this:

0x01through0x1A= A through Z0x1Bthrough0x34= a through z0x80through0x89= 0 through 90xFF= line break

So the letter “A” isn’t 0x41 (ASCII), it’s 0x01. tile #1 in their font tileset is the letter A. Once you figure out the mapping, decoding is just a big if/elseif:

if ($byte >= 0x01 && $byte <= 0x1A) {

$result .= chr(ord('A') + $byte - 1);

} elseif ($byte >= 0x1B && $byte <= 0x34) {

$result .= chr(ord('a') + $byte - 0x1B);

} elseif ($byte >= 0x80 && $byte <= 0x89) {

$result .= chr(ord('0') + $byte - 0x80);

}

it works.

The Graphics

Game Boy tiles are 8×8 pixels with 4 shades of green (well, gray on the actual hardware… the green was just the screen). Each pixel needs 2 bits to store its shade (0-3), packed in a format called 2bpp (2 bits per pixel).

Here’s how one row of 8 pixels is stored in 2 bytes:

Byte 1 (low bits): 01011010

Byte 2 (high bits): 00110110

^^^^^^^^

Pixel: 01001310 (combine bit from each byte)

For each pixel, grab one bit from byte 1 and one from byte 2, combine them, and you get a value 0-3. In PHP:

for ($row = 0; $row < 8; $row++) {

$byte1 = ord($this->data[$address + ($row * 2)]); // low bits

$byte2 = ord($this->data[$address + ($row * 2) + 1]); // high bits

for ($bit = 7; $bit >= 0; $bit--) {

$pixel = (($byte1 >> $bit) & 1) | ((($byte2 >> $bit) & 1) << 1);

// $pixel is now 0, 1, 2, or 3

}

}

Each tile is 16 bytes (8 rows × 2 bytes per row). So every 16-byte chunk in the graphics region is potentially a tile.

ASCII Art in the Terminal

Before even bothering with images, you can preview tiles right in the terminal:

$shades = [' ', '░', '▒', '█'];

echo $shades[$pixel];

That one line turns pixel values into a quick visual.

Actual PNG Output

Once you know the pixel values, GD handles the rest:

$image = imagecreate(64, 64);

// Classic Game Boy green palette

$colors = [

imagecolorallocate($image, 155, 188, 15), // lightest

imagecolorallocate($image, 139, 172, 15),

imagecolorallocate($image, 48, 98, 48),

imagecolorallocate($image, 15, 56, 15), // darkest

];

imagefilledrectangle($image, $x, $y, $x + $scale - 1, $y + $scale - 1, $colors[$pixel]);

imagepng($image, 'tile.png');

Actual Game Boy sprites rendered as PNGs from raw ROM data. Using PHP’s GD library.

Assembling Multi-Tile Sprites

Individual tiles are only 8×8 pixels. Scrooge McDuck is bigger than that. Characters are usually made up of 4 tiles (2×2 = 16×16 pixels) or 6 tiles (2×3 = 16×24 pixels).

The tricky part is figuring out HOW the tiles are arranged in memory. Left-to-right? Top-to-bottom? Interleaved? Some weird order specific to Capcom? We don’t know, so… trial and error:

$patterns = [

'sequential' => [0, 16, 32, 48],

'interleaved' => [0, 32, 16, 48],

'column_pairs' => [0, 16, 256, 272],

'reverse' => [48, 32, 16, 0],

];

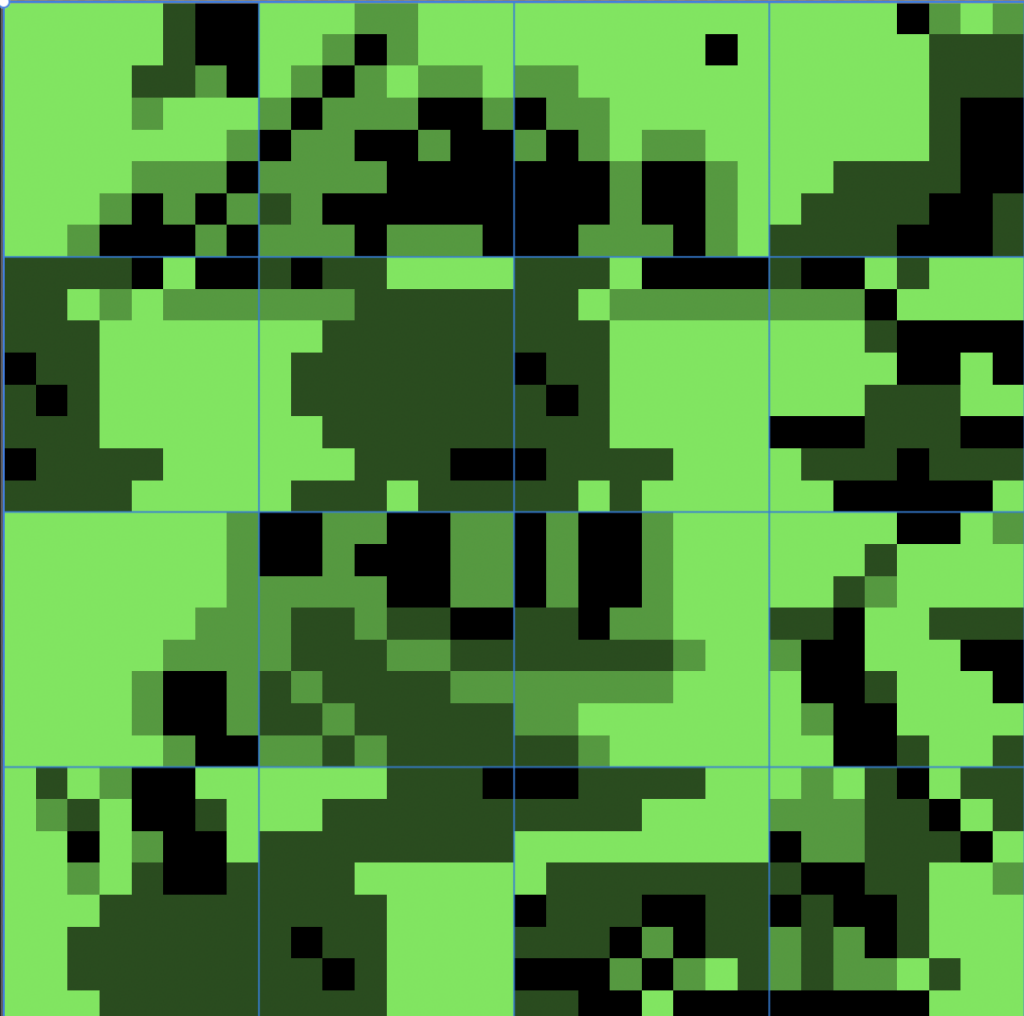

Each array is 4 byte offsets from a base address, placed into a 2×2 grid. Generate a PNG for each pattern, look at the results, and one of them will look like an actual character. It’s not elegant, but it gets the job done. For example, below is one of the extracted spritesheets… and you can sort of seen Scrooge elements in the center:

Here’s a screenshot from the actual game, and while some coloring is different, you can see elements…

Decompressing Hidden Graphics

Not all graphics are stored raw. Capcom used LZSS compression to fit more data into the ROM. It’s a fairly simple scheme with two operations: literal runs (“copy the next N bytes as-is”) and back-references (“copy N bytes from earlier output, starting M bytes back”).

The token format is one byte:

- Bit 7 clear → literal run (lower 7 bits = count)

- Bit 7 set → back-reference (lower 7 bits = length, next byte = offset)

0x00→ end of data

while ($pos < $this->size) {

$token = ord($this->data[$pos++]);

if ($token === 0x00) break;

if (($token & 0x80) === 0) {

// Literal: copy next N bytes directly

$count = $token & 0x7F;

for ($i = 0; $i < $count; $i++) {

$output .= chr(ord($this->data[$pos++]));

}

} else {

// Back-reference: repeat from earlier output

$length = $token & 0x7F;

$offset = ord($this->data[$pos++]);

$srcPos = strlen($output) - (256 - $offset);

for ($i = 0; $i < $length; $i++) {

$output .= $output[$srcPos + $i];

}

}

}

The interesting part is finding compressed blocks. We scan the entire ROM, try to decompress at every offset, and check if the result looks legit (decompressed size is bigger than compressed, output is a multiple of 16 bytes so it contains complete tiles). It’s bruteforce, but it turns up graphics you’d never find otherwise.

Finding Level Maps

Level layouts are stored as tile maps… grids of numbers where each number says “put tile #X here.” The game’s rendering engine reads these grids and draws the level by looking up each tile.

We scan for regions that look like tile map data using a pretty basic heuristic: if a block of bytes mostly contains values between 0x00 and 0x7F (valid tile indices), it’s probably a tile map.

for ($i = 0; $i < 32; $i++) {

$byte = ord($this->data[$addr + $i]);

if ($byte > 0x00 && $byte < 0x80) $score++;

if ($byte == 0x00) $score += 0.5;

}

if ($score > 20) {

// Probably a tile map

}

Once you have a map address and know where the tileset is, you can render an entire level preview by looking up each tile index and drawing it:

$tileId = ord($this->data[$mapAddr + ($y * $width + $x)]);

$tileAddr = $tilesetAddr + ($tileId * 16); // 16 bytes per tile

// Decode and draw that tile at position (x, y) in the output image

Right now this handles all the data in the ROM: graphics, text, maps, compressed blocks. I think the next step is a full CPU disassembler for the Sharp SM83 (the Game Boy’s processor). So turning every byte in the code regions into readable assembly instructions, which I’m not sure if even possible?

Anyway… there’s literally no reason to do this, and I have no idea what I’m trying to accomplish.